In 166 AD, Chinese historians recorded that an ambassador from the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius arrived in the Chinese capital of Luoyang. The travelers arrived via Malaysia, along the coasts of Thailand and Vietnam, and anchored at a Chinese port at the mouth of the Red River in the Gulf of Tonkin. They then traveled nearly 2,000 kilometers by land. The Han nobles and officials were eagerly anticipating the visit of the foreigners. The Chinese had long known about the Roman Empire. They called it the Great Qin, considering it their equal in power. But this was the first time the two ancient empires had come into direct contact.

However, when they met the ambassadors, they were disappointed because they brought only “trifles” picked up in Southeast Asia: ivory, rhinoceros horns, and tortoise shells, nothing that evoked the splendor of Rome. The emperor and his court suspected that they were simply Western merchants living in Asia and not emissaries of the Roman Emperor. They also wondered why Western travelers were passing through Vietnam. The usual East-West route was via the Gansu Corridor, which linked the Yellow River basin with Central Asia. The explorer and diplomat Zhang Qian traveled to Central Asia via the Gansu Corridor in the second century BC, and that fertile land later became an important part of the Silk Road.

In the West, interest in the great trans-Asian route began centuries ago. The Western footprint in Central Asia dates back to the time when Alexander the Great led his army as far as the Indus River and founded several cities in the region (327 BC). However, the first commercial contacts with the Far East were established by sea, from the Egyptian port of Alexandria, under the Ptolemies.

Discovering the route from the shipwreck

The sea route to the Near East was discovered by accident. A patrol boat in the Red Sea found a drifting boat carrying a dying man. No one could understand what he said or where he came from, so they took him back to Alexandria. When the lucky man learned Greek, he explained that he was an Indian sailor and that his boat had drifted off course. The Egyptian king (Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II) gave command of the Indian expedition to the explorer Eudoxus of Cyzicus. At court, Eudoxus learned about the shipping routes along the Nile and the unique wonders of the Red Sea. Thanks to his keen observation, he quickly learned from the Indian sailor how to cross the Indian Ocean. The key was to take advantage of changing seasonal conditions: the monsoon winds blew from the southwest to India from March to September, from the northeast to Egypt from October to February. Following the instructions, Eudoxus successfully sailed from Egypt to India in just a few weeks. After exchanging gifts with the rajas (chieftains or kings), he returned to Alexandria with his ship laden with spices and precious stones. Eudoxus' pioneering voyage opened up a fascinating new world to his contemporaries. Merchants from both the East and the West were quick to take advantage of the opportunity to trade across the Indian Ocean.

The Peutinger map shows the Roman road network that ran through the empire in the 4th century AD. The easternmost section is shown here. The Temple of Augustus is shown (bottom right) next to the city of Muziris in India, just to the left of the oval lake. Source: AKG/Album

Alexandria International

After the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, Alexandria became the main port for goods from the East. After landing on the Red Sea, goods were transported by camel to the Nile and by boat to Alexandria, from where they were distributed throughout the Mediterranean. Syrians, Arabs, Persians and Indians became common faces on the streets of Alexandria.

All goods and people had to pass through the city of Koptos (also known as Qift), a commercial center on the banks of the Nile. From here, several caravan routes set out across the Eastern Desert of Egypt towards the Red Sea. An inscription at Koptos records that caravan members paid different fees according to their profession. For example, craftsmen were required to pay 8 drachmas, sailors - 5, soldiers' wives - 20, and prostitutes - 108 drachmas. Caravans would travel through the desert at night to avoid the extreme heat. They could stock up on water and food at military posts along the route.

The busiest ports on the Red Sea were Myos Hormos (Quseir al-Qadim), over 100 miles east of Koptos (5-6 days' journey), and Berenice over 250 miles south (12 days' journey). Caravans from Greece, Egypt, and Arabia converged on these ports to pick up ivory, pearls, ebony, eucalyptus, spices, and Chinese silk from India. They sent ships back to India loaded with wine and Western goods. During Roman times, the ports were always busy.

Red Sea to Indian Ocean

A merchant’s handbook on the Indian Ocean dating from the mid-first century BC (Periplus Maris Erythraei) mentions the main ports of call in India: Barygaza, Muziris, and Poduke. The rajas attracted many visitors to these ports, as well as merchants, musicians, concubines, intellectuals, and priests. Muziris, for example, was so crowded with foreigners that a temple was built in honor of Augustus, the first Roman emperor. A young student from Alexandria might now decide to venture across the Indian Ocean instead of traveling the Nile.

Artifacts found along the Silk Road

Few, however, ventured beyond India. The Periplus Maris Erythraei asserts that silk originated in China and was transported overland across the Himalayas to the port of Barygaza. The Chinese were called Seres (silk workers), but few ever saw them. Many Romans knew nothing of silkworms and believed silk to be a vegetable fiber. Westerners knew of a distant country that produced a fine fabric, which they brought back to be woven with gold thread in Alexandria or dyed royal purple in Tyre. But its exact location remained a mystery.

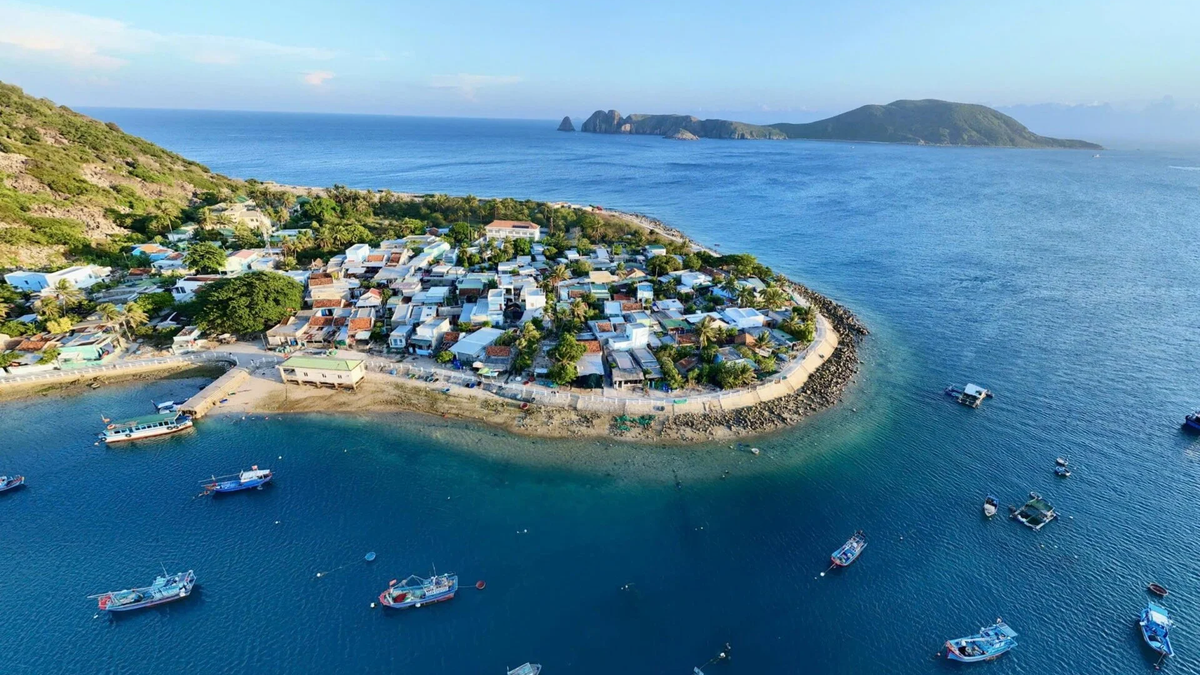

Once in India, merchants did not usually go straight to China. They first stopped at Taprobane Island (Sri Lanka), then crossed the Strait of Malacca to Cattigara (Oc Eo) in the Mekong Delta in our country. Here, many precious stones carved with Roman motifs and medals bearing the images of the Roman emperors Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, along with Chinese and Indian objects, were found. These findings suggest that Oc Eo was a bustling commercial center, and this opens up the possibility that the people believed to be Roman ambassadors representing the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius at Luoyang were actually merchants from Oc Eo.

Source: Nationalgeographic

Translated by Phuong Anh

Source: https://baotanglichsu.vn/vi/Articles/3096/75446/tu-la-ma-toi-lac-duong-huyen-thoai-con-djuong-to-lua-tren-bien.html

Comment (0)